|

Folk Dance Federation of California, South, Inc.

|

|

CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE

In the late 1970s, Gary and Susan Lind-Sinanian began to document dance among Armenian, Turkish, Kurdish, Arabic, and Assyrian émigrés and communities in North America. Forrest Johnson, Katherine St John, Dr. Lloyd Miller, and Ara Topouzian also have collected and shared copious information about Armenian dance and music. Many thanks to them all for invaluable information. The many errors and generalizations of this article occur in spite of their best efforts and belong to me, alone!

In the days before the Romantic Nationalism movement and Western Cultural Imperialism destroyed ethnic identities and killed millions of people for the sake of artificial ethnic purity and profit, the peoples of the Levant1 such as Armenian, Kurdish, Arabic, Assyrian, Jewish, Turkish, and Druze enjoyed similar dances to similar music based on geographic REGIONAL boundaries, not ethnic or political. Thus, peoples of the Great Armenian Plateau of Eastern Anatolia danced the bar (see the 1996 Problem Solver) and other types of dances, peoples of the lowlands to the southeast danced the Sheïkhani (see the 1999 Problem Solver) and other types of dances, and so on, each region having its own repertoire and style, with some dances occurring in many regions.

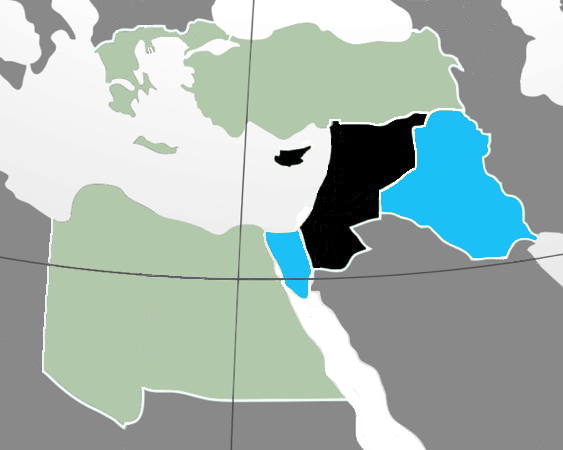

1 The Levant is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, it is equivalent to the historical region of Syria, which included present-day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Palestine, and most of Turkey southeast of the middle Euphrates. In its widest historical sense, the Levant included all of the Eastern Mediterranean with its islands, that is, it included all of the countries along the Eastern Mediterranean shores, extending from Greece to the eastern coastal region of Libya.

Hidden Agendas

Following the bloodbaths of the 19th and 20th centuries, national academies began to classify the dances of their nations, occasionally employing a classification scheme that emphasized an ancient claim to their lands (and their neighbors' lands!) or reified a direct descent from an ancient culture. (One must wonder who will be the first to claim direct descent from Cro-Magnons!) Turkish classifiers, for instance, identified dances by region. Thus, they classified the bar known as Yaylalar (see the 1999 Problem Solver), as a halay because it comes from the Halay dance region. On the other hand, Armenian theorists noted that the bari-yerker (song-dances, see Sirun Gakav in the 1989 Problem Solver) occurred most frequently. Thus, they used linguistic dialects as categories. The same tamzara, for instance, would be categorized differently according to the dialect of its lyrics. While both Turkish and Armenian specialists recognize the shortcomings of these systems and study dances by their underlying structure, they have little impact on the "official" categories.

Speculation

Much Soviet Armenian research emphasized an ancient fertility ritual basis for Armenian dance. Because the surviving fragments of Armenian dance in the United States and around the world have become highly secularized, even among the oldest informants, this basis remains speculative and less than useful for the international folk dancer trying to understand Armenian folk dance.

Bar v. Gyond v. Govand

In classical Armenian, barel meant "to move in a circle," i.e., the Divine Liturgy instructs the priest to do the bar around the altar, meaning to lead a religious procession, not to dance. However, since most Armenian folk dances move in a semi-circular pattern, the term evolved into the verb "to dance" in most regional dialects. In circle dances, the barabed (dance leader) kept the circle intact, not allowing dancers into the circle or to break away into a new circle until the song ended. In regions that danced in straight lines rather than circular (e.g., Van), the word bar did not acquire that newer meaning, and the older classical term gyond remained the word for "dance." Gyond also evolved into the term govand, a class of dances often but not always related to the halay. For example, people of the Lake Sevan area call their graceful Mom Bar (candle dance) a govand, but the Lind-Sinanians teach it as Mom Bar to avoid confusing folk dancers unfamiliar with govand.

The Regional Styles

International folk dancers in North America possibly will have encountered five identifiable styles of Armenian music and dance: İstanbul Armenian, Western Armenian, Levantine Continental, Eastern Armenian, and Armenian-American.

Istanbul-Armenian style

This region lies in the urban areas of İstanbul in which Armenians reside, but also includes all regions of present-day Turkey and the diaspora in which Armenians dance such dances.

Instruments include the oud (short-necked, plucked-string lute), kanun (trapezoidal, plucked dulcimer ancestor), and kemenche (bowed spike fiddle). Kanun players, masters of Ottoman music, played at court and throughout Armenia. Kemenche also occurs across Armenia.

Dances: Bolsetsis (Armenians from Turkey) favored solo and couple dances over line dances, but now, Armenians everywhere dance solo dances. Solo dancing, however, does NOT mean belly dancing! Turkish culture relegated belly dancing, to low-class Greeks, Armenians, Jews, and Moslems. Ghawazee (dancing women) came from the North African Oulid Nail tribe, Salubba (Bedouins of Arabia), and Romanis. Although the flood of American housewives embarrassingly anxious to perform in the Middle East weakened this traditional attitude in the 1970s, the social stigma persists today, up to the top of the profession where stardom erases your past, creating ambivalence about the art and the artists.

Western Armenian Regional Style

This region, the Armenian Plateau and homeland before 1915, has the cities of Erzerum, Kars, Van, Trebizond, Mush, Elaziğ, Sepastia/Sivas, Drabizon, Diyarbekır, Garin, and others. The shorter and stockier Western Armenians, with the classic Armenoid skull and profile, reflect Uratian and Assyrian ancestry. Most Armenians in America of the first large wave (1915-1925) came from Western Armenia during its genocide. This regional style remains popular in the United States, although with a more mellow sound and subdued drumming after the arrival of the second wave, described below.

Linguistically, the Western Armenian dialect uses aspirated consonants such as D, G, and B.

Instruments include davul, a large frame drum played with club and switch, that frequently accompanies the zurna, an oboe-like instrument dating back several thousand years. These instruments remain ubiquitous in Turkish folk dance music, but the modern Armenian American band supplanted them in America in the 1950s.

On V-J Day (the end of the Second World War, August 14, 1945), the entire Armenian community of Watertown, Massachusetts marched to the State House (about 7 miles), led by davul and zurna.

The classical santur (triangular hammered dulcimer ancestor) died out in 1915, but other instruments include the saz (long-necked, plucked lute, like the tar in the east), dig (bagpipe), oud, and kemenche (bowed spike fiddle).

Dances of the Plateau include bar-type dances. The zaghareet, the vocal trilling, did occur rarely in some of the Armenian dances to the extreme west and south, but not on the Plateau or in adjacent regions. When it did occur, it reflected Arabic influence, not Armenian.

Levantine Continental style

This region comprises refugees, primarily from the 1915 genocide, residing in the Levant: Beirut, Alleppo, etc. Some 85 percent of these refugees came not from the Great Armenian Plateau but from the south: Adana, Marash, and Aintab, and spoke Turkish or Arabic, not Armenian.

Musically, these Armenians rejected both Western Armenian peasant traditions as low class and İstanbul Armenian culture as Ottoman. Perhaps because of the French legacy of the Levant, they embraced a "Continental" style of music: French popular melodies with Armenian lyrics. Starting in the 1960s, the Hamizkine Association collected old music and reissued it in Continental guise – Latin rhythms, snare drums, and electronic instruments – to appeal to their Levantine public. (Note that Lebanese Christians, Maronite and Melkite, similarly rejected Arabic culture for French.) The 1975-1990 Civil War in Lebanon brought this Levantine Continental music to the United States, primarily to the West Coast, with a second wave of immigrants who denigrated Armenian American music of the first wave as "Turkish."

Ironically, French-Armenian music confuses most Armenians. Much of it is ashoog (troubadour) music, but several of the songs are traditional bari-yerker (dance-songs) used while dancing.

Eastern, Kavkaz Regional Style

This region comprises the former Soviet Armenia. Once an outpost, this mountainous stronghold became the Armenian foster homeland after 1915, from which Armenians gaze longingly at their native Mount Ararat, only 40 miles across the border. Cities include Yerevan (Erevan in transliterated Russian), Zangezour, and Urmia. Eastern Armenian dancers appear taller and slimmer than the Western, partly because of intermarriage with Westerners and partly because Soviet dance masters wanted that body morphology for their folk ballets. Most Armenians in America of the third (1990-2001) wave came from Eastern Armenia, following the collapse of the Soviet Bloc.

Linguistically, Eastern Armenia uses the unaspirated consonants T, K, P, J, and TS.

Instruments of Eastern Armenia include the def (frame drum), duduk (mey, narr, balaban, etc., a clarinet-like instrument with huge double reed), tar (long-necked, plucked lute, like the saz in the west), and kemenche. In Eastern (Soviet) Armenia, the Anatolian kanun supplanted the santur after 1915. Dueling ancestral dulcimers? Probably more a case of changing musical tastes and VERY abrupt population movements.

The dance of most Armenians in the diaspora follows the Eastern Armenian style to establish a distance from Turkey, yet the style they follow, the back arches and high arms and innocent air and wisp of a smile, derive from the Yerevan Choreographic School where instructors balanced Armenian nationalism and Socialist dogma. Traditional Kavkaz (Caucasian Mountains) women kept solemnly expressionless when dancing lest they be thought shameless and a disgrace to their family's honor.

Armenian-American style

This region centers on Los Angeles and Fresno on the West Coast, Detroit in the Mid-West, and Boston and New York in the East, but its influence appears in international folk dancing and in Armenian communities across North America.

Instruments: Piano(!). Yes, every Armenian church had a piano, so Armenians before the second wave accept piano for nostalgic reasons. The modern Armenian-American band formed in the 1940s with the oud, kanun, dumbeg, violin and rural clarinet (for zurna), and conga and bongo drums, a combination made possible by electronic amplification. The use of conga (originating on the East Coast) and bongo drums died out as they faded from American society in general.

Dance: Armenian-American youth added claps and turns to dances and augmented the standard Armenian repertoire with the Shuffle (see the 1996 Problem Solver) and the Hop (see the 1997 Problem Solver). West Coast dance competitions sponsored by the Armenian Church inspired new Armenian dances such as Siroon Aghcheek (Sweet Girl) (see the 1996 Problem Solver), Guhnega (see the 1994 Problem Solver), Garoon, Ambee Dageets, and Heeng oo Meg.

Others

Armenians spread wide during the diaspora, e.g., to South America, but those communities have not influenced North American international folk dancing.

Conclusion

The more you learn about the styles of Armenian music and dance: İstanbul Armenian, Western Armenian, Levantine Continental, Eastern Armenian, and Armenian-American, the more you will enjoy and appreciate the fantastic breadth and depth of Armenian culture and dance.

References

- Beliajus, Vyts. Viltis, December 1962.

- Johnson, Forrest. Personal communications, in Society of Folk Dance Historians Archives.

- Lind-Sinanian, Gary and Susan. Dance Armenian, 2nd ed. Newton, MA: Middle East Folk Arts Cooperative, 1978.

- ----. Articles on Armenia dance in Viltis: 39:4 (December 1980), 40:5 (January 1982), 44:5 (January 1986), 45:2 (June 1986).

- ----. Personal communications, in Society of Folk Dance Historians Archives.

- Miller, Lloyd, and St John, Katherine. Personal communications, in Society of Folk Dance Historians Archives.

- Topouzian, Ara. Personal communications, in Society of Folk Dance Historians Archives.

- Various encyclopedias and gazetteers.

Used with permission of the author.

Printed in Folk Dance Problem Solver, 2001.