|

Folk Dance Federation of California, South, Inc.

|

|

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

This article defines recreational international folk dance (RIFD) as the social practicing of dances

chosen intentionally from several cultures other than your own.

Attempts to write the history of RIFD appeared in the 1991 and 1996 Folk Dance Problem Solver (PS).

A Russian Forebear? (pardon the pun)

Tsarist Russian ballroom dances utilized foreign motifs. For example, Espan (PS 1990 and 1991) and Pas D'Espan (PS 1991) show Spanish influence, Hiavata or Hiawatha (PS 1991) mimics Native Americans, Karapyet (PS 1991) utilizes Armenian or Georgian themes, Kokietka (PS 1991) resembles a French polka, Korobushka (PS 1988) uses Hungarian motifs, and Lezginka (PS 1990) borrows from Daghestan or Georgia. These dances achieved recreational international folk dance (RIFD) popularity in America, but no evolutionary link has appeared between the Russian ballroom and the beginnings of American RIFD.

'Aesthetic dance'

(H'Doubler, 1925. The Dance. NY: Harcourt, Brace & Co. p. 60)

Educational Beginnings

Mary Wood Hinman [1877-1952], a pioneer in women's physical education, taught dance in her Chicago home in 1894 and later established public physical education programs (Odom. "Sharing the Dances of Many People." Proceedings of the Society of Dance History Scholars, 1987, p. 65). She presented ethnic dance, gymnastic drills, social dance, and the so-called 'Greek' aesthetic dance. Luther Gulick [1865-1918], New York City (NYC) Physical Training Director, observed Hinman and championed folk dance to counter youth crime and ethnic bigotry (The Healthful Art of Folk Dancing. New York: Doubleday, 1911). His disciple, Elizabeth Burchenal [1876-1959], with Hinman, Nils Bergquist, C. Ward Crampton, and Caroline Crawford, established the folk dance literature with dances learned from observation of natives and from each other's books. For decades, educators used these dances from Europe, Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Native America, and European America.

Intercultural understanding and respect grounded Hinman's efforts. As recently-established émigrés from Western Europe discriminated against the more-recently-arrived émigrés from South and East Europe, folk dancing mitigated that discrimination. As did Hinman, Burchenal strove to build ethnic pride by maintaining ethnic veracity in her rush to publish newly described dances and new editions of her books. Ironic, is it not, that her legacy rests largely on physical education, rather than on her pioneering ethnographic dance research.

The "War to End All Wars"

During and after the Great War, refugees brought to America the songs and dances of their homelands. Folk dancing again mitigated ethnic bigotry as Settlement Houses, caring for the destitute newcomers, soon found that appreciation of ethnic heritage enhanced immigrant self-image and facilitated social acceptance. YWCA International Institutes promoted ethnic appreciation, as did ethnic cultural societies. With a notable exception, however, immigrants of this era had small influence on the development of RIFD. That notable exception? European dance teachers.

European Dance Teachers

Following the War, European dance teachers augmented the RIFD repertoire with their imports and creations. Vytautas Finadar "Vyts" Beliajus [1908-1994] presented realistic Lithuanian, Jewish, Hindu, and Mexican exhibitions derived from his life in Europe and from ethnic groups with which he worked. Interestingly, the concern for the human condition and respect for other cultures displayed by Hinman, Gulick, and Burchenal pervaded Beliajus' seven-decade career, perhaps accounting for some of his enduring popularity among the perceptive. Vasiľ Avramenko [1895-1981] studied folk and theatrical dance with Nikolay Karpovich Sadovskiy in Kiev before bringing to North America the dances Arkan, Hopak, Zaporozhets (PS 1987, 1988, & 1994), and other magnificent Ukrainian character and folk dances. Louis H. Chalif [1876-1948] choreographed balletic character dances quickly forgotten or changed, such as Pletyonka (PS 1988) and Troika (PS 2000).

Re-creating Recreation

Perhaps as a result of the War, America turned inward in a search for wholesome recreation. Following British models, Anglo-American dance revivals occurred. Mary Neal and Cecil Sharp had organized their English dance societies before the War and were teaching and researching dance in America (PS 2001, p. 4). In 1923, Jean Milligan and Ysobel Stewart founded the Scottish Country Dance Society. Mr. and Mrs. Henry Ford revived square dancing in 1925, publishing their much-cited dance manual Good Morning in 1926. Of the Danish folkehøjskole movement that came to America in 1871 (www-distance.syr.edu/stubblefield.html), two schools affected RIFD. In 1925, Olive Dame (Medford) Campbell and Marguerite Butler founded the John C. Campbell Folk School in North Carolina. Georg and Marguerite (Butler) Bidstrup emphasized at the school the concept of Danish folk dance as recreation, presenting, for example, Napoleon, Sekstur, and Maskerade (PS 1993). From 1928 to 1938, Chester and Margaret Graham directed the Ashland Folk School in Michigan, and they invited notable teachers such as Hinman and Burchenal to visit The Eighty-Year Experience Of A Grass Roots Citizen. Muskegon MI: Graham, 1977). The Grahams introduced folk recreation to Lynn and Katherine Rohrbough of the Cooperative Recreation Service (Hampton to Houston, December 12, 2001 e-mail, in Society archives), who published hundreds of booklets and books of dances and songs, many used by RIFD. The recreation movement continues, frequently with RIFD in the program.

Cooperative Recreation Service, Delaware, Ohio

Stella Marek Cushing [c.1898-1938] organized in 1931 what I believe to be the First RIFD Club in the world, the Cosmopolitan Club of Montclair, New Jersey (PS 2004). Cushing's student, Rose Grieco [1915-1995], directed the club until 1995, and Rose Grieco's sister, Barbara Grieco, continues it to this day. The University of Chicago's 1932 International House also qualifies as one of the first RIFD groups (Helen Pomerance Johnson. "Where Int. Folk Dancing Began," Viltis 51:6 (March-April 1993), p.3), because the group started before 1932 in the basement of sisters Charlotte 'Chili' (Lewis) Chen and Maxine 'Jerry' (Lewis) Joris Lindsay. Beliajus taught the Chicago group during the 1930s and 1940s, and other prominent RIFD leaders later led that group.

RIFD Exhibitioners

Folk festivals figured prominently in efforts to integrate immigrants into American society. Burchenal, for example, had presented thousands of her girls in annual pageants such as the 1921 'America's Making' exposition. Folk festivals retained their popularity into the Great Depression, providing entertainment for which the public would pay and, inadvertently, contributing to the development of RIFD clubs, as follows.

To improve inter-ethnic relations, Thomas L. Cotton [1891-1964] of the Foreign Language Information Service formed the New York Folk Festival Council in 1931, providing a platform for personalities such as Elba (Farabegoli) Gurzau, who presented RIFD favorites such as Il Codiglione, La Danza, and Tarantella Napolitana.

Alice Sickles began the Saint Paul Festival of Nations in 1932 (Florence Johnson. "Festival of Nations' 60th Anniversary." Viltis 50:6 (March-April 1992), p.9). Beliajus presented his Lithuanian troupe at the 1933-4 Chicago Exposition, focusing on the Lithuanian dances he later popularized among international folk dancers. Sarah Gertrude Knott [1895-1984] organized the National Folk Festival Association in 1934. Many international folk dance leaders presented and acquired dances at these festivals, including Beliajus, Dick Crum (below), Nelda Guerrero Drury, and Morry Gelman, who introduced Croatian Waltz (PS 1990 & 1992), which he learned at Knott's 1949 festival.

Song Chang [1891-1974], entranced with the humanistic values of folk dancing (Larry Getchell, A History of the Folk Dance Movement in California, Folk Dance Federation of California, 1995, p. 2), formed California's first RIFD club in San Francisco in 1937. 'Chang's', the only international club amid national clubs, exhibited dances at the 1939 San Francisco World's Fair. Virgil Morton [1913-1981] taught the club most of their dances until shipped off for World War II, at which time Morton trained Madelynne Greene [?-1970] as his replacement (Beliajus. "Virgil L. Morton." Viltis 40:1 (May 1981), p. 24).

As the most enduring contribution of these years, Pat Parmalee of the NY Folk Festival Council asked Avramenko's student (and tenant), Michael Herman [1911-1996], to teach folk dances at the 1939-40 New York World's Fair. He emphasized audience participation, leading directly to the 1940 founding in NYC of his Community Folk Dance Center, later known as Folk Dance House, successful for almost half a century (Michael Herman's Odyssey. NYC: Herman, undated). The enduring nature of Herman's contribution lay in the many leaders who learned from him and in his provision to RIFD of folk dance records, discussed below.

RIFD Magazines

The Depression also saw the founding of RIFD magazines. Folk News, the voice of New York's Folk Festival Council (see above), emerged in the 1930s. From 1941 to 1947, Herman published The Folk Dancer, closely imitating Folk News in format, scope, and quality.

The Folk Dancer, Michael Herman, Publisher

World War II witnessed more magazines. Beliajus started Viltis ("hope" in Lithuanian) as a newsletter to maintain contact with men and women serving in the military, his Lithuanian friends, and folk dancers. Viltis, the only long-term, nation-wide voice of RIFD, continued until Beliajus' death in 1994, when the International Institute in Milwaukee assumed publication. In 1944, the Folk Dance Federation of California founded its magazine, The Federation Folk Dancer (usually called the Folk Dancer), but quickly changed the name to Let's Dance when Michael Herman complained of infringement. Let's Dance continues. From 1945 to 1957, Rod La Farge [1905-1978] started his iconoclastic and perceptive Ramapo Rangers, renamed in 1946 as Rosin the Bow. From 1949 to 1984, Ralph Page [1903-1985], the 'Dean of New England Contras and Squares', published his very personal and informative Northern Junket. From 1954 to 1956, Hugh Thurston in England edited the scholarly The Folk Dancer. Let's Dance, Ontario Folk Dancer, Northwest Folkdancer, Southern California's Folk Dance Scene, and the Report to Members of the Society of Folk Dance Historians currently inform RIFD'ers nationwide. Many RIFD periodicals have appeared, some as advertising organs for record vendors or leaders. In my opinion, the survivors were those that avoided too-rapid growth or full-scale parthenogenesis.

RIFD "Advances" Through "Retreats"

In about 1940, noted recreation leader Jane Farwell [1916-1993] interned in NYC, met and studied dance with Michael Herman (above), and lost Michael to Mary Ann (Bodnar) Herman [1912-1992]. Farwell followed the Hinman-Gulick-Burchenal humanist approach and used RIFD as a vehicle for recreation. In 1940, she began the folk dance retreat or 'camp' movement at Oglebay, West Virginia. Pinewoods Camp (1915) in Massachusetts and Berea College (1920s) in Kentucky predated Oglebay but focused in their early years on Anglo-American heritage rather than RIFD.

In 1948, Walter Groethe (familiar with Pinewoods) and Mary Ann Herman (familiar with Oglebay) inspired Lawton Harris [1900-1967] to found Folk Dance Camp at College of the Pacific in Stockton, California. 'Stockton' continues, virtually unchanged but for the growth of live music and the change from College to University.

Farwell imparted recreation to the Hermans through workshops that led, in 1948, to Maine Folk Dance Camp. 'Maine Camp' lasted until 1994, at which time Michael (Mary Ann had died) closed the site, discouraged over perceived mismanagement, disrespect of primary-source dance teachers, record piracy, and the replacement of folk dances with novelty dances (Herman to Houston, personal communications, in Society archives). Mainewoods Dance Camp supplanted Maine Camp in 1995 and continues.

Roy McCutchan [1919-2006] met and married Elizabeth "Zibby" (Wolfolk) McCutchan [1915-1983] while square dancing (and studying) at the University of Texas at Austin, 1939-1941. During World War II, Zibby moved to San Francisco with Roy, a naval officer conducting chemical engineering research, and discovered Chang's. After the war, the McCutchans initiated many of the RIFD groups and camps in the American Southwest: Austin (continuing the group started when Marlys (Swenson) Waller and Anne M. Pittman invited Leon McGuffin to their women's physical education class at UT), San Antonio, Corpus Christi, Marshall, Los Alamos, and derivative groups in Galveston, Dallas, and Oklahoma. Meanwhile, Margaret (Clark) Thompson, Waller, and Pittman had attended Oglebay. In January 1949, they organized and invited Farwell to staff Texas Folk Dance Camp. Thompson developed a family, so Roy and Zibby continued to guide 'Texas Camp' by Farwell's principles, withdrawing in 1973 over the loss of recreation, such as the replacing of local musicians with hired musicians. In August, 1949, the McCutchans founded the Los Alamos Folk Dance Camp, which ran for at least 10 years. Idlewilde Camp 'jes' growed' from the early 1950s to the late 1970s under McCutchan care.

Farwell founded Folklore Village at her family farm in Wisconsin to provide folkloric recreational weekly gatherings and several festivals each year. For example, Christmas Festival, founded in 1948, presented Farwell's alternative to a commercial Christmas, celebrating the twelve days of Christmas in five. (Bacharach to Houston, January 11, 1997 letter, in Society archives). Martin Bacharach conducted the Festival during Jane's absences. Folklore Village continued under new leadership after Farwell died in 1992.

Madelynne Greene (above) taught at Maine Camp in 1962 and embraced the recreational approach to folk dance. She and Scottish dance teacher C. Stewart Smith [1929-1982] founded the Madelynne Greene Folklore Camp that year. In 1964, the camp moved to a permanent home at Mendocino Woodlands and flourished. When Greene died, Gordon Engler and Nora Hughes joined Smith in managing the camp until 1972, when Smith moved to Texas. Dean and Nancy Linscott organized the next administration with Honora Clark and Joan and Dale Dunleavy. The Linscotts retired in 1989, and the camp continues under new leadership.

Mexican Professor Alura Flores Barnes de Angeles ([1905-2000], see the PS 1993) was discovered and introduced in the 1940s to RIFD camps by her student Nelda (Guerrero) Drury. Flores, with Farwell, Drury, David Houston, Ron Houston, Manuel and Odilia Gomez, and other dear friends from Texas, founded Festival Folklórico Internacional in central Mexico in 1971. Flores' health declined significantly in 1992, and 'Mexico Camp', always a struggle, foundered without her personal and political influence.

Sound Recordings

Up to the 1930s, the piano accompanied most folk dance classes. With a few notable but ineffective exceptions, the halcyon days of educators Hinman, Burchenal, Bergquist, Crampton, and Crawford had devolved into a community of 'muscle mechanics' maintaining a self-perpetuating repertoire only remotely connected to RIFD. Records helped, but some records "did not inspire the dancer or teacher." (Michael Herman's Odyssey, p. 6) Of the ethnic records that did exist, early RIFD'ers used any recorded music available, sometimes with amusing consequences: "Look! You can Hambo to this Italian waltz!"

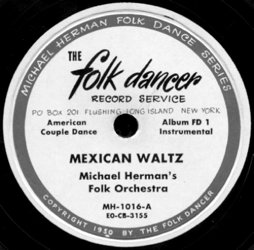

After World War II, three RIFD-oriented record companies captured much of the RIFD market for 78 rpm records: Folk Dancer (19%), Folkraft (11%), and Imperial (7%). Victor (11%) and Columbia (7%) also sold well in those days. The popularization of microgroove records in the mid-1950s saw the market shares shift as Folkraft outsold Folk Dancer, Imperial, Victor, and Columbia combined (based on relative numbers of tens of thousands of 7" and 10" records donated to the Society archives).

The Folk Dancer Record Services

Square dance caller Frank Kaltman and Dan Wolfert started Folkraft in New Jersey in 1946. Rickey Holden joined Kaltman in 1951 and founded Folkraft-Europe in 1967. Folkraft produced more square dance music than other RIFD record vendors and targeted educational as well as RIFD markets. The educator Olga Kulbitsky wrote many of the dance directions for Folkraft. Folkraft-Europe now has licensed Syncoop of the Netherlands to release many of its recordings on CD.

Paul Erfer, pianist and outgoing dance teacher, learned much of his dancing from Michael Herman in NYC and founded the seminal Hollywood Folk Dancers when he moved to California (Gelman to Houston, June 17, 1993 letter, in Society archives). Erfer produced with Imperial Records a series of Nationality Albums specifically for folk dancers. In many instances, these were the first recordings made in the U.S. of many folk dance melodies, allowing RIFD groups that relied on recordings to expand their repertoires. Erfer arranged the music, and the musicians would wear at least one piece of the national costume to put themselves in the proper ethnic mood.

Michael Herman, trained in folk dance by ethnic groups and in classical violin by Juilliard faculty members, collected and sold the available ethnic records and encouraged the recording of others. When record companies discontinued their ethnic lines, he founded with the help of Dave Rosenberg the Folk Dancer label in NYC in 1948 and produced several hundred excellent folk and contra dance recordings, frequently with Michael on violin, Mary Ann on piano, and the extraordinary Walter Eriksson on accordion. The Folk Dancer label sold primarily to RIFD'ers. In 1997, Herman's heirs gave to the Kentucky Dance Foundation over 35 tons of Herman's phonograph records, and the KDF has made some of those recordings available on CD (Shacklette to Houston, November 15, 1997 letter, in Society archives).

John Filcich founded the Festival record label in California, which sold as well as Victor and Folk Dancer during the microgroove era. He also provided copies of rare recordings to the RIFD community, occasionally earning censure from the owners of those recordings. The Worldtone label by Kenneth Spear in New York had almost as large a market share as Festival.

Veteran RIFD'ers will recognize the labels of a number of specialty companies: Windsor records founded by Doc Alumbaugh, Kismet, Sonart, MacGregor, Balkan, and others. Walter Kögler of Germany toured North America in 1967, introducing his Tanz recordings. Paul and Gretel Dunsing and Farwell used Tänz and Tänz der Völker records extensively in the 1960s, giving RIFD many of its North European dances.

The availability of tape cassettes in the late 1960s virtually destroyed the folk dance record industry. To his dying day, Michael Herman eagerly awaited the development of a cassette that would self-destruct when used to duplicate a record (Herman to Houston, personal communications, in Society archives). Theft of recordings so bothered Herman that he virtually refused to sell his records for the last 20 years of his life. This refusal, however, only exacerbated the theft. Some say that cassettes also contributed to the decline of RIFD itself. You see, every 'generation' of copied music loses about 10% of its fidelity. The first cassette copy of a record starts at 90% fidelity, the copy of the copy at 81%, and so on. RIFD'ers accepted the gradual decrease in quality. Newcomers, however, did NOT accept it, and some may not have continued in RIFD because of it.

Expansion to England

British schools traditionally had presented the 'play' of other cultures, particularly Western European (Goddard to Houston, November 14, 2004 e-mail, in Society archives). In the 1930s, British folklorists such as Maud Karpeles [1885-1976], John Kennedy, and Philip Thornton [?-1992] explored the world, particularly the Balkans (Peter Kennedy to Houston, August 3, 2001 e-mail, in Society archives. See also Thornton's books: Dead Puppets Dance (1937, pp. 132-3) and Ikons and Oxen (1939).) and brought home folk songs, rituals, and dances.

In London, World War II brought together British students, European refugees, and a folk dancing American soldier named Nat Brown. England's Society for International Folk Dancing grew from this association, and RIFD still flourishes in Britain.

Expansion to Japan

Although foreign dance entered Japan in 1883 with the Rokumeikan Dance Institute (Koshimizu. "Rokumeikan dance and its influence: mainly upon girls' high school for 100 years." Rokumeikan Dance Institute, October 30, 1993), RIFD came only after World War II with visiting religious and relief missions (Hiroyuki Ikema to Houston, December 17, 1993 letter, in Society archives). Thanks to Rickey Holden (August 23, 2001 e-mail, in Society archives) for much of the following account.

First came Warren Nibro, a U.S. Army Recreation Specialist stationed in Tokyo and Sapporo after World War II, who had danced with the Hermans in NYC. Nibro recognized that RIFD could (and did) cut vertically through what had been a rather strictly horizontal social structure, furthering the official U.S. policy of democratizing Japanese society.

Second, Pan-Am sent air traffic controller Larry Keithley and his wife Joanne Keithley to Japan. From Chang's in San Francisco, they started a regular group in Tokyo, building on the foundations laid by 'Nibro-san'. Attendees included Prince Mikasa (youngest brother to the god-king Emperor Hirohito) and Mikasa's wife, Princess Mikasa (Yuriko) Takagi. Such patronage received much publicity and public acceptance as the 'brother of god' held hands with and used the same forms of address as people some dozen or more social levels below him.

The Keithleys award a diploma to Prince Mikasa. June, 1952

(Photo from Owen King)

Third, in 1956, Earl Buckley, General Secretary of the Tokyo YMCA, convinced the U.S. State Department and the newspaper chain Asahi Shimbun to bring Michael and Mary Ann Herman, Nelda Guerrero Drury, Ralph Page, and Jane Farwell on a teaching tour in which he also participated. RIFD increased greatly as a result of this incredibly successful tour, and Buckley continued to promote RIFD as one of the functions of the Japanese 'Y'.

The last of the great pioneers, Rickey Holden, taught folk and square dance in all the major population centers of Japan during his world tours of 1958 and 1960-62, also with publicity from Asahi Shimbun.

Expansion Worldwide

During his world tours, Holden spread RIFD (and traditional square dancing) across much of the Orient, the Middle East, Europe, and Latin America. He established a residence in Belgium in 1961 and continues to teach and to organize dance seminars worldwide.

In 1948, after much petitioning, the Dutch queen granted two Americans, a Canadian, and two Dutch a half-hour audience. Three and one half hours later, she granted them funds to establish what became the Nederlandse Volksdansvereniging (Nevo, or, Dutch Folk Dance Association), which became the Landelijk Centrum voor Amateurdans (LCA, or, National Center for Amateur Dance). Graduates have studied with native ensembles (below) to create hundreds of dances to sell to U.S. RIFD'ers.

Folklore Ballets

Igor Moiseyev's Soviet folkloric ballet inspired similar troupes around the world: Filip Kutev in Bulgaria, Kolo in Serbia, Lado in Croatia, Tanec in Macedonia, Mazowsze in Poland, Amalia Hernández in Mexico, and thousands more. Typically, the best dancers, singers, and musicians from local ensembles would graduate to regional ensembles, and the best of the regional ensembles would apply to the national ensembles.

Beginning in the 1950s, these troupes toured North America. RIFD'ers eagerly accepted stage creations such as Kolo's Serbian Medley #1 and Tanec's Šopska Petorka, increasing the aerobic content as well as the tempo and color of RIFD. Usually, the theatrical nature of stage dances obscured their ethnographic content, as witnessed by the apocryphal quotation of one ensemble choreographer: "I am an artiste; not a peasant!"

Crum visited Yugoslavia in the early 1950s, observing state ensembles and social dance events. He was artistic director for the Duquesne University Tamburitzans under Walter Kolar from 1955 to the late 1960s and made dance a much larger portion of their repertoire. The Tammies' Serbian Medleys, Croatian Medleys, and Bulgarian recordings such as Bučimiš and Sedi Donka still appear in popularity polls 30 years and more after their introduction.

Partner Dances

After World War II, the new supply of ethnic phonograph records allowed returning soldiers, sometimes with their new ethnic in-laws, to flock to RIFD leaders such as Beliajus, the Dunsings, Farwell, the Hermans, and Rosenberg. Perhaps RIFD popularity sprang from the urbanization of post-War America and a resultant yearning for rural activities as a war-weary country sought (again) to re-create itself. Perhaps Americans enjoyed the huge post-War increase in leisure time. Or perhaps it sprang from a new awareness of other countries coupled with a decrease in xenophobia brought on by the certain knowledge among millions of returning soldiers and sailors that America was the mightiest nation on earth. Americans reached out to other cultures through RIFD.

These teachers expanded the largely couple dance repertoire of Hinman et al. as RIFD began to acquire many dances directly from Europe. The Dunsings introduced German dances. Farwell introduced dances of North Europe. The Austrian Student Goodwill Tour to North America of 1949-50 and the Second Goodwill Tour of Austrian Students and Teachers to North America in 1950-51 introduced many delightful Austrian dances, including the Zillertaler Ländler (PS 2000) to incorrect but readily available music. In about 1948, Gordon Tracie [1920-1988] began to research folk dance in Scandinavia and later taught or re-introduced such well-known favorites as Fyramannadans (PS 1991), Hambo, and Fjäskern. Native Scandinavian teachers then visited or moved to the U.S. to continue the 'Scandi' movement. Elizabeth Rearick, Alice Reisz, Andor Czompo, Csaba Pálfi, and Judith and Kálmán Magyar introduced stirring Hungarian dances. In 1966, Germain and Louise Hébert introduced the first significant body of French folk dances to the U.S., including Eggbeater Bourrée (PS 1993).

Muscle Mechanics, Part 2

The 'baby boom' following World War II apparently surprised America, and massive spending on schools, teachers, and curricula followed. The 'Cold War' that followed World War II maintained a national emphasis on physical fitness for America's future cannon fodder, and folk dancing in the public schools grew. The early folk dance literature gave way to a new literature designed for gym teachers, largely unschooled and uncaring about the context of folk dancing. "Cookbook" folk dance texts of the era usually included a name for the dance, alleged country of origin, step description, and source. The better books would include a bit about history and culture and suggest a curriculum. Notable examples include the voluminous and long-running Dance A While, started in 1950 by Jane A. Harris (replaced in 2005 by Cathy L. Dark), Anne M. Pittman, and Marlys (Swenson) Waller, the more contextual but undocumented Teachers' Dance Handbook by Olga Kulbitsky and Frank Kaltman (1959), and the seminal Folk Dance Progressions by Miriam D. Lidster and Dorothy H. Tamburini (1965) that incited my interest in classifying dances by patterns of weight transfers. Books of this era drew from the RIFD movement and, in turn, served as RIFD references. Unfortunately, few gym teachers danced, and such books served as their only source of information. In the 1970s, the ethnic diversity movement entered the educational system, and these books provided the needed material, serving much the same need as the folk dance books of a half-century before.

Non-partner Dances

In 1945, RIFD had perhaps less than 1% non-partner dances. Now, most group repertoires contain less than 1% couple dances. Why?

'Kolos' and other extremely vivacious and attractive non-partner dances appealed to the expanding female RIFD population during the 1950s. Note that RIFD anticipated by a decade the essentially partner-less nature of American popular dance, which may account for some of the popularity of RIFD in the 1960s as it satisfied a growing societal need. These non-partner dances came, in general, from the Middle East and from the Balkans.

Part of Palestine became Israel in 1948 and exported a number of dances, many of them non-partner and most of them based on 1920s modern dance as practiced by the German Zionist movement, the Blau-Weiss Bund [Blue-White Group] (Judith Brin Ingber. "Shorashim: The Roots of Israeli Folk Dance." Dance Perspectives 59, Autumn 1974). Viennese modern dancer Fred Berk (né Friedrich Berger) immigrated to NYC and founded contemporary Israeli recreational dance there in about 1951, based largely on some 13 American Zionist and 38 Palestinian/Israeli dances (PS 1999, p. 4). From such modern dance origins came the RIFD practice of performing Israeli dances barefoot. The halutsim (pioneer) tradition declined in Israel around 1960, so the energetic 'national' dances of the halutsim gave way to subtle folk dances based on traditions of the ascending Sephardim (African and Asian) and Hassidim (Orthodox European) classes. With the 1970s Disco craze came 'Israeli disco' dances, few of which survive in RIFD.

In 1950, Beliajus started 'kolomania' in California by presenting eight kolos at Stockton Folk Dance Camp. In 1951, The Hermans added others, and 'Kolo John' Filcich organized the first Thanksgiving Kolo Festival in San Francisco. He and his family continue to run Kolo Festival, and kolomania persists to this day as the 'Balkan' music and dance movement.

In 1951, Frances Ajoian began to present Armenian dances to RIFD. These dances achieved popularity primarily in Southern California where Ajoian lived, but later inspired national teachers such as Tom Bozigian and Gary and Susan Lind-Sinanian.

In 1953, Anatol Joukowsky [1908-1998], a classically trained European ballet master with a deep interest in folk dance, began to present ethnic line and partner dance motifs set to stirring music. His dances still appear on RIFD popularity polls: Gerakina, 'Ajde Jano (PS 1987), Vrtielka, Horehronsky Čardáš, Senjačko Kolo, Katya (PS 1997), and Jabločko (PS 1990), to name but a few.

In 1953, Olga Veloff Sandolowich studied folk dance in Bulgaria with the ensembles of Koutev and Haralampiev and brought back versions of Daičovo, Graovsko, and Bavno. Michel Cartier followed in the late 1950s with such dances as Ekizlijsko (PS 1989), Partalos (PS 1995), Dajčovo, and Jambolsko Pajduško Horo (PS 1997). In 1964, Atanas Kolorovski slightly preceded George Tomov, both significant Macedonian teachers. Yves Moreau followed these in about 1970, and many of his dances, Bulgarian and later, Breton and French-Canadian with wife France Borque-Moreau, still support the international folk dance movement, decades later.

In 1954, Larisa Lucaci supervised 10 Romanian dances on the Folk Dancer label and eventually presented 21, such as Alunelul (PS 87) and Dura (PS 94). Other teachers followed: Eugenia Popescu-Judetz, Sunni Bloland, Mihai David, Alexandru David, and Nico Hilferink taught hundreds of additional dances utilizing Romanian motifs.

Turkish dances began to appear in about 1964 with Cavit Kangõz. In 1970, Bora Özkõk began to introduce dozens more.

By far, the greatest single non-partner push in RIFD came from Dick Crum [1928-2005], quite simply the finest folk dance teacher in the world by virtue of his huge intelligence, his encyclopedic knowledge, and his boundless and gracious tolerance of students. Drawing inspiration from the pre-war writings of Philip Thornton (above) and from the American ethnic communities of his youth in Saint Paul and Minneapolis, Crum began in 1954 to import dances from the Balkans. Interestingly, Crum early taught Slovenian couple dances but rapidly shifted to non-partner dances from Serbia, Croatia, and Romania. His research interests included virtually all of Europe.

The Flood

Although RIFD'ers had been complaining since the early 1950s about the influx of new dances, the 1960s brought a veritable flood of researchers, recordings, workshops, and choreographers that doubled and quadrupled the number of dances available to RIFD. Advances in communications and transportation technology facilitated this flood as long-distance telephony became common and as airplanes replaced ocean liners. The 1960s folk and counterculture movements propelled the flood with their emphasis on tolerance of other peoples. Note, please, the similarity to Hinman, Gulick, Burchenal, and Beliajus, providing an alternative to ethnic prejudice and discrimination.

RIFD Rifts

In the 1950s, the natural union between domestic and international folk dancing dissolved as square dancing and round dancing became it's own movement, Modern Western Square Dancing (MWSD), with hundreds of newly-devised figures and series of required classes. RIFD kept many academic dancers and a few traditional square and round dances, but RIFD'ers generally avoided MWSD.

In the 1970s, clogging separated from Southern Mountain/Appalachian square dancing into its own splinter movement, drawing heavily on contemporaneous tap dancing. The weekly television comedy revue 'Hee-Haw' sponsored contests that accelerated this development.

Contra dance, a living New England tradition preserved in part by Ralph Page and documented largely by Rickey Holden, developed its own following in the 1970s. Choreographers re-invented, borrowed from other cultures, devised on the dance floor, or designed on computers thousands of dances to a variety of new tunes, e.g., Hills of Habersham (PS 1987). Tony Parkes has stated that his 1972 Shadrack's Delight started modern contras, a group of dances in which 'inactive' couples dance as much as 'active' couples. RIFD always contained some American dances, for example, Salty Dog Rag (PS 1994), but dwindling attendance in the 1990s compelled many traditional RIFD groups to adopt newly-devised contra dances in hopes of imitating contra dance's popularity. Instead, RIFD may have hastened its own demise due to 'Shields' correlation': "Dance movements cease to grow when they become so complex that newcomers must take more than about six lessons." (Lysle Shields Jr. to Houston, March 29, 1994 e-mail, in Society archives)

In the late 1970s, Hungarian dancing developed into the separate Táncház movement, largely through the teaching of Judith and Kálmán Magyar.

Scandinavian dance began to diverge in the late 1970s as Dean and Nancy Linscott produced several 'Valley of the Moon' weekend workshops with teachers and musicians from Sweden and Norway and with the very popular Gordon Tracie from Seattle. 'Scandi' separated in 1980 with the first 'Scandia Camp Mendocino' under the leadership of Nancy Linscott, encouraged by Swedish dance and culture teachers Ingvar and Jofrid Sodal.

In the late 1980s, Richard Powers almost single-handedly created the Vintage Dance movement, comprised of American and European dances of the mid-19th through 20th centuries. While RIFD continues to incorporate much 'Vintage' in its repertoire, some dancers left RIFD to devote more time to specialty dances.

In the late 1980s, Roy Hilburn began to teach Cajun dance to RIFD. He also introduced Zillertaler Ländler motifs to Cajuns, inspiring an entire corpus of dance movements.

Until the late 1980s, country-western line dancing consisted primarily of Ten Pretty Girls (PS 2003) and the line-dance version of Cotton-Eyed Joe (PS 1990) followed by a line-dance Schottische. By 1993, the movement had mushroomed to dozens of dances, and by 1995 to hundreds, most of them ignored by RIFD.

Musical Evolution

Mark Levy became one of the first Americans to master and encourage others to master ethnic Bulgarian musical instruments, adding a new dimension to Balkan dancing. Bands with ethnic instrumentation appeared across the country, supplanting the short-lived migration from records to accordions and other less-than-pure folk instruments.

Why the Decline in RIFD?

Many people have proposed reasons for the decline in RIFD. Nelda Guerrero Drury and Richard Duree implicate the loss of college folk dance courses resulting from budget cuts caused by the 1972 oil embargo. Without that influx of young people, the movement aged, repelling yet more young people. Others, reminiscent of Burchenal, blame performance: "The true richness of folklore always runs the risk of being reduced to glossy banality whenever traditional forms are used in modern choreography." (Gross. "When Folklore And Aerobics Collide." Washington Post, March 18, 1996, p.D8). Dancers have blamed since the early 1950s the increasingly large and sophisticated repertoire required to satisfy the need in many dancers for personal excellence in smaller fields. A few, unaware of the vital cultural context of folk dance, blame restrictive cultural values: "Why shouldn't women dance men's dances?" "Why shouldn't men wear dresses?" Old-timers note that the great leaders died: Hinman, Burchenal, Farwell, Beliajus, and the Hermans, leaving good teachers but not great leaders. Folk dancers, occasionally a libidinous lot, seem to need to follow the perception of a strong moral example. Finally, I sometimes like to define folk dance as the dance of your grandparents. Does this imply that folk dance music lacks musical relevance?

I feel that these explanations distill to a more fundamental cause of RIFD decline: the shift from a movement of outwardly-directed tolerance and understanding to a movement of inwardly-directed personal gratification. For example:

- National organizations meet, but they discuss revenue, rather than engage in dance.

- Local groups cover lack of research with the isolationist "We dance it differently in our village."

- Local leaders isolate their groups from the larger RIFD world, seeking to protect their share of the dwindling attendance.

- Local musicians strive to be more authentic than native musicians, an example of Umberto Eco's 'hyper-reality' (Travels in Hyperreality, 1986).

- Beginning dancers seek multiculturalism but find (and must join) cliques.

- Second-year dancers seek recognition on the stage.

- Third-year dancers seek recognition as teachers.

- Fourth-year dancers seek recognition as master teachers! Gimme a break!

Revival

The reasons that RIFD should wither are legion. Yet, against them all, I will pit one reason that it might endure: Hinman's folk dancing began on, and could return to, the road to understanding and tolerance of other cultures. Folk dancers as a group possess a larger than average view of the world and of the world's history. If WE cannot see the need for a return to consideration of others, who can? Friends, even the literal resurrections of Hinman, Gulick, Burchenal, Beliajus, and Farwell would not revive folk dancing! It's up to YOU, and you alone.

Used with permission of the author.