|

Folk Dance Federation of California, South, Inc.

The Intersection |

|

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Background and Philosophy

The sixties were a time of ferment and cultural rebellion in Los Angeles. People yearning to embrace humanity, suspicious and insecure of the future, were searching for roots and meaning. It was a period of questions before the bombardment of the electronic age. The Intersection was a place where many cultural phenomena could be found, a place that transported each of us into a safe, private, and real world. There, people discovered the essential spirit of a true "folk experience" through expressions of music, song, and dance -- no gimmicks, no gestalt psychology or parapsychological fantasies -- we aimed at creating a unstructured happening where events and situations would evolve giving the impression that we were not programmed. Even the celebrations we coordinated were prescribed to unfold as an organic experience. Events developed according to who was present. Some referred to our evening functions and the dancing that took place as if they were accidental. They were indeed spur-of-the-moment, always infusing an element of surprise with the mix of the dancing. Any resemblance to organization would have been wrong. Soon, we learned to recognize the value of spontaneous activity, how enriching and valuable it was.

The sixties were a time of ferment and cultural rebellion in Los Angeles. People yearning to embrace humanity, suspicious and insecure of the future, were searching for roots and meaning. It was a period of questions before the bombardment of the electronic age. The Intersection was a place where many cultural phenomena could be found, a place that transported each of us into a safe, private, and real world. There, people discovered the essential spirit of a true "folk experience" through expressions of music, song, and dance -- no gimmicks, no gestalt psychology or parapsychological fantasies -- we aimed at creating a unstructured happening where events and situations would evolve giving the impression that we were not programmed. Even the celebrations we coordinated were prescribed to unfold as an organic experience. Events developed according to who was present. Some referred to our evening functions and the dancing that took place as if they were accidental. They were indeed spur-of-the-moment, always infusing an element of surprise with the mix of the dancing. Any resemblance to organization would have been wrong. Soon, we learned to recognize the value of spontaneous activity, how enriching and valuable it was.

True, The Intersection appeared on the scene at a time when the greater Los Angeles community was ripe for it. Though we did not foster a specific structure, we were careful to nurture different cultural experiences, viewing them as fresh and brand new, by revitalizing the folk customs that retained vital expression and by inviting everyone to share in them regardless of background. We knew then and there that we needed to safeguard what was unfolding and not to insert any artifice. We wanted to "open the doors" in a way that assured all could "turn native" easily, even for a brief moment.

Our program was simple: the early part of the evening at The Intersection was dedicated to folk-dance instruction as well as other similar folk oriented workshops in singing, folk arts, costumes, and even ethnic cooking, in the atmosphere of an old-time village cafe. Later in the evening, the patrons were left to their own devices, and because they were not aficionados, they would make mistakes, confusing cultural idioms at times, but it was important not to curtail the creative impulse. The "folk arts" are a creative expression; a collective art revealing composite evocations expressed within a community, encouraging a personal artistic expression by everyone sharing a commonality in being the "folk artists."

Urban communities lack the ambiance and camaraderie inherent in traditional village life. Individuals often are isolated from interaction with one another. Folk singing and dancing connect people creatively by expressing innermost feelings and imagery. The collective creative process creates fellowship through social functions and rituals. The modern meaning of "folk" is the unpretentious sharing of various cultures. Like celebrants in a cathedral, they discover a greater unity with fellow members of their congregation in a shared ambiance of folk art. The Intersection drew from such functions and facilitated the "intersecting" with a variety of folk forms and with other cultural expressions, as well.

Beginnings

Four people got together one day toward the end of 1964. They were Louise (Anderson) Bilman, Rudy Dannes, Chalo Holguin, and Marilyn Sage (who later married Chalo). They met at the apartment building of Louise and her daughter, "Kit," and sat by the swimming pool to discuss a folk dance situation: They wanted a place to have more hours of dancing after the regular folk dance groups quit for the night at 10:30 p.m. (the groups stopped at that time because the janitors needed to come in to clean the meeting spaces!).

They came upon a low rent storefront at 630 N. Alvarado Street in Los Angeles, California, just off the 101 Freeway, not quite downtown – an obscure location by Los Angeles standards. They put down $3,000.00 to secure the building. That was the start of "The Intersection." Although the coffeehouse opened its doors in March, 1964, its official opening was late August. Rudy Dannes did all the artwork. Rudy's mother, Lily, who was very active in the startup of the business, suggested that the front of the building needed curtains and volunteered to make them. To safeguard the place, Rudy offered to be the watchdog and made it his temporary living quarters. Rudy, Demo Dafnos, George Nichols, and I cut the "windows."

Rudy and I became the managers, directors, teachers, coffee brewers, and custodians. Mini pizzas, rice pudding, and baklava were our only menu offerings. A cover charge of 35 cents per person went into our first cash register, a tin can that we jingled as people appeared at the door. With it came coffee and free refills. Soon however, we discovered that when each evening came to an end, everyone would instantly disappear, leaving Rudy and myself with the cleanup. We summoned our members to a meeting and insisted that this vanishing act stop.

We never sought to create a club, cafe, studio, or business, but simply to create a little "home" where we could dance into the morning. Before The Intersection, we continually searched for places to dance and conducted sessions in high-school gyms, where custodians promptly turned the lights out and cut our dancing short.

We had a core group of friends who shared our passion for folk dance. As a performing group, we called ourselves the Hellenic Dancers. I was the director and Rudy was my excellent right hand. Still burning with desire, we would whirl into cafes for a continuation of our "dance bonding." At times, we would end up at Greek nightclubs where we had to put up with fancy shows and pop singers who belted out the latest songs from Greece. Occasionally, nightclub owners would let us dance between the floorshows and belly dancers' acts whose thirty-minute sets garnered dollar bills from rowdy onlookers and heavy drinkers who tossed money like confetti. Gouged by cover charges and two-drink minimums, we found that our participation soured. Restlessly, we looked for a spot somewhere in the Los Angeles area to call our own, somewhere where the rent would be manageable for a dozen or so "members." Monthly dues would cover expenses, and all would share in the chores.

With a place of our own, the word spread, and small crowds who were not part of our Hellenic Dancers dropped by to dance with us. Rubi Vučeta – a social worker by day and an avid Balkan dancer by night – was a spitfire who shared our philosophy about folk dance. Ruby held a Balkan Night every Wednesday at the Hollywood Recreation Center. Her periodic visits to Jugoslavia gave her an insight into the vitality of our visitors and she was thrilled to move her group rehearsals to our storefront. Monday nights with the Greeks and Wednesday nights in the Balkans with Ruby attracted curiosity seekers as if they were visiting an underground speakeasy, even though all we served was coffee. Ruby's sudden death in an auto accident in Europe startled us. For many years afterwards, her spirit and glow remained within The Intersection and her legacy was well endowed in her many followers.

Our storefront off the 101 "Hollywood" Freeway instantly became a stomping ground for folk dancers from all over; along with them came new recruits and people discovering folk dancing for the first time. Some people even crossed Doheny, a main thoroughfare dividing Beverly Hills and the Westside from the "common folk" of the Hollywood area. Soon college students, educators, and professionals regularly visited The Intersection. Schoolteachers started bringing their classes to introduce their students to other cultures, and high school students became a new breed of folk dance enthusiasts, while college students found a home away from home. It was a time when travel abroad was cheap and students easily backpacked through Europe and the Middle East. The Intersection was part of that exploration as young people had their first foreign encounter before leaving home, fortifying them culturally.

Recent European immigrants became regular habitués, finding a welcome opportunity to share their traditions with new American friends. On one occasion, a young Greek college student wanting to impress some newly acquired friends bragged: "Let me show you some hasapiko steps I've been dancing all my life." After watching closely, another friend quickly pointed out that he had just learned those steps at The Intersection last week! Embarrassed, the young student meekly walked to a corner and waited for another round of dancers to impress. Television producers and film directors would bounce in and try a few sessions, often selecting dancers for various shows and big-time movies taking place in North Africa and other exotic locations. A score of Intersectionites danced in the movie What Did You Do In the War, Daddy? In the remake of The Postman Always Rings Twice starring Jack Nicholson, the celebration scene with authentic Greek folk music of the thirties starred Intersection Dancers.

The Intersection was crowded every night; cars lined the street. Suddenly this area – which had been dead – had now come to life, with people popping in from every corner of Los Angeles. One night, after seeing the traffic jam outside, police unexpectedly broke in and wanted to know why was everyone so "high." Sure – we were high on coffee and folk dancing, which was a high that could make us reach Olympian heights! Age didn't matter. Octogenarians Millie Libaw in her red Hungarian boots and the arid, rough-edged Mike Tzavaras – who swore The Intersection added ten years to his aging life – were constant patrons, nightly winning the admiration of young people. They adored Mike's style – his overflowing white mustache that he loved to twirl – and he was always encouraged to solo dance the Greek Zeimbekiko. Before making his way onto the dance floor, he'd pull a "George Burns" and playfully pinch a young lady. A retired café owner, his daily routine was to hang around the Hollywood fast-food stands that newcomer Greeks owned or managed. He would regale them with stories about "the smartest Greek in town," who has a cafe with only a coffeepot on one side and phonograph on the other while he stands in the middle collecting dollar bills. The place is packed; his pockets are bursting!

Some time later, while visiting family in New York, I stopped by Michael and Mary Ann Herman's Folk Dance House in Manhattan to teach a Greek dance workshop. I admired Michael and Mary Ann, and their contribution to folk dance has been invaluable. They were the pioneers of international folk dancing in America, exposing thousands to folk dance and making available music and instructions. I felt honored when they invited me to teach, but they had a required method of presentation that I couldn't pursue in disseminating the special quality of the improvised moment in Greek dance. I had spent a couple of years as an instructor at Arthur Murray's doing precisely that, and I couldn't be part of any cookie-cutter dance routine instruction. During this visit, Michael and Mary Ann were anxious to find out what The Intersection was all about. The word was out; it had reached New York. They asked what were we doing there in California that held everyone so mesmerized. I truly didn't know how to answer them, so I just smiled.

Other folk dance leaders trying to uncover our secret formula besieged us. They wanted to open similar establishments. We were astounded and, in no time, we were involved in meetings, negotiations, working arrangements, and above all, requests for us to hand over our secret ingredient insuring them a successful operation. Encouraged by our success, other entrepreneurs began similar dance places in Pasadena, the Valley, West Los Angeles, and Orange County. Yet there was no magic, no secret formula, no technologies, and no imbibing blessed libations, but this lack of method just added to our mystique.

Expansion

From my earliest exposure to Greek dance, I was attracted to the inherent qualities fostered in ceremonial rituals – the foundation of the earliest forms of theater – and how the sacred dance evolved to secular functions that we find in folk dancing today. Rudy and I spent many hours exchanging views. We espoused a unique folk dance experience, not always agreeing, but we were excited by the results we achieved and explored expansion of The Intersection concept. We aimed to reach the essence and spirit of each culture and to recreate an environment similar to that in which traditional folk life had thrived.

You see, dance is an organic art, a living sculpture that releases the spirit and character of individual "folk" artists. Does every pianist play Bach alike? Does every conductor interpret Mozart the same way? To encourage the art, we felt it important to dance to live music, as well as to a variety of new tunes from the broader selection of recorded music. The tune or melody does not dictate the form or style of the dance – rhythm does – and there are many varied melodies for dance rhythms. The waltz and tango have many different melodies, as do Greek dances, and I was sure it would be true for other cultures as well. The time had come to introduce the concept of creative folk dancing, not always restricted to set patterns. For example, I could never accept the Vari Hasapiko as a set routine danced to the same melody every time. I taught routines to beginning students in order to initiate their interest and give them something to lean on, but eventually I would encourage their creative impulses to experiment.

Once, some heavyweight attorneys who thought this could be a great franchise idea approached us. They offered to work out arrangements, establish several centers in the area, create and train staff, and eventually go national. They would handle the franchise and stock options and so on. Rudy and I thought we had taken a short hop to the moon and back. We were not sophisticated stock capital franchise moguls, and we could not comprehend their mumbo-jumbo. They were flabbergasted that we didn't leap at the opportunity and dance deliriously down Wall Street, celebrating and waving beautifully engraved stock certificates like hankies during a Kalamatiano. When we forgot to reply to them, we received a bill for a three-hour consultation fee, though they had initiated the meeting!

We never considered expanding or moving from our little hovel on Alvarado until city officials beset us with requests to comply with city ordinances, apply for licenses, carry insurance, etc. We were confronted with such rules as: two men cannot dance together and no dancing with a lit cigarette in your mouth. In the early sixties, before smoking became such a health and political issue, no one could imagine dancing the Zeimbekiko without a cigarette in the mouth – it was a given prop to the dance and often not lit. More and more inspectors would arrive, asking us to apply for more licenses. We asked why all this flurry and inquiry – what provoked it? They answered that several parties were applying for new business permits and when asked what kind of business, they said they wanted to open a business like The Intersection! Finally, the city ordered us to shut down because we didn't comply with the ordinance of occupancy and lacked a second door as an exit – the Alvarado store butted against a hillside. We requested an extension and we immediately went scouting for another location.

Adequate space within the rental price range we could afford was impossible. I recalled conversations my father often had with his friends that in business, unless you strive to own a building, the rent would eat you alive. After many months, Rudy and I located a piece of property near downtown, on Temple Street, close to the Hollywood freeway. Rudy, an experienced structural design draftsman, began planning and working with architects to design and build a place we could call our own, with all the appropriate permits, so no one could budge us in the future. Of course, there are a multitude of construction headaches, but it all boils down to money, and our budget was tight, and I mean tight. There are many tales, but the dumbest was when – in order to save money – we decided to demolish the dilapidated wood frame house on the property ourselves, nearly toppling it on our heads!

Greece

We solved the problem of location, but often solutions breed new problems. After opening, we were perceived as successful businessmen and were besieged with offers for partnerships and consulting. Our partnership ventures were disasters, total failures. We soon discovered that entrepreneurs like to be their own bosses and don't want others looking over their shoulders, even though they liked having the comfort and assurance that we would help them get started. Afterward, they wanted to be off on their own. Unfortunately, being naïve, we fell into the trap and suffered losses.

One example came in the early seventies when I was approached about having a similar place in Athens. I thought it might not be a bad idea. I had enjoyed considerable success with Greek dance in the United States and thought this might be one way of continuing my relationship with both countries and a way of honoring my good fortune. The Intersection in Athens opened in the Plaka area below the Acropolis, a rather Bohemian "Latin Quarter." I was elated. What could be better than dancing under the stars within view of the Acropolis and Parthenon? Very early, my idealism – like Isadora Duncan's – soon faded. Some seventy years before, she abandoned her garments on the ancient marbles and danced naked in the Parthenon. She was politely but angrily covered and swept away. My folly required new and expensive permits. Though we paid the official fees to Greek authorities, the police reminded us that we could not play music after 10:00 p.m. – it disturbed the neighbors. So we paid fines and were exhausted by summonses. I also differed conceptually with my Athenian partners. I had thought we were to have a place similar to the Los Angeles Intersection, but they wanted only a nightclub. Athens was rampant with nightclubs hawking entertainment to tourists; failure in 1974 was predestined. Of course, my Greek associates weren't going to listen to me coming from America telling them how to handle Greek dance and music in Greece! My only consolation was that I had been firm in that Rudy would not invest his own money or Intersection assets in this expansion effort. I was emotionally attached to Greece and had a right to speculate, but I could never explain to Rudy the Byzantine intricacies of doing business in Greece. After a couple of years, The Intersection in Athens totally flopped. I lost my investment, but was happy – I had tried.

Temple Street Troubles

With the new building on Temple Street, "business" went well. No more tin cans, no more relying on congenial friends dropping by. We had to overcome the awkward position of reminding "friends" – especially those who supported us the first three years – of our need to function as a business. We had mortgages, permits, insurance, operating costs, and more, but folk dancers barraged us by asking for special treatment. "Why can't we come in and just dance? Why should we pay admission? After all, folk dancing is free; it belongs to everyone! Why are you capitalizing on traditions? Why are you such mercenary capitalists?" Our rebuttals were short and unacceptable to our clientele consisting of college students, low scale income earners, and a handful of questionable leftovers from the hippy culture. We toughened our resolve to survive in business and meet the demands, become taskmasters, promote business, pay off loans, etc. In addition, the city's bureaucratic haranguing continued: more licenses, more permits, insurances, fire codes, and health permits. Each inspector would contradict the previous.

We had to constantly reinvent to keep up, yet avoid being commercial and remain true to what we set out to accomplish. Our own personal dance activity and artistic involvement with dance groups diminished. We had business to attend to and we were learning as we went. I went to Greece one summer to prepare the Athens Intersection. I returned to glance over my mail, messages, and bills, and there was an official-looking man waiting outside our building. As I attempted to put the key in the door, he beamed at me and asked most politely, "Excuse me sir, are you Mr. Karras?" "Yes," I replied. "May I see your hands?" he blurted. I promptly held out my hands for him, whereupon – in a flash – he placed handcuffs on me and started to march me off. "Why?" I said. "What's up?" "You haven't paid your payroll taxes, and the IRS is placing you under arrest," he replied. I didn't have the seven hundred plus dollars on me, but he was willing to follow me to my office for my checkbook. He drove me to the bank and stayed glued to me as I cashed a check to pay him. Unfortunately, our accountant had ignored all the IRS requests forwarded to him for the couple of months of my absence.

More and more, Rudy and I found ourselves spending time to remain in business and naturally less and less time on our personal quests with folk dancing and what we enjoyed. We were constantly reinventing the wheel. Almost every outstanding folk dance leader and personality was invited to headline an event. We offered recordings and international gifts, expanded the menu with ethnic cuisine, and aimed to be an international bazaar or emporium, but we lacked the skills in promotion and marketing. The Intersection became a talent pool for newly formed dance troupes and a Mecca for anyone trying to find out about ethnic cultures. So many lives were touched, and there are thousands of stories to be told, some great, some terrific, a few sad tales, but it's best that secrets be kept. We were delighted so many patrons found their significant other at The "I." To this day, people stop me to tell me, "I don't know if you know it but I met my wife (or husband) at the Intersection. Thank you!"

Conclusion

What determines the life span of a business, especially of restaurants or clubs? People are fickle, and so many new activities constantly bombard the public, all vying for the same entertainment dollar. By the early eighties, lifestyles had changed dramatically. Discos enticed with titillating laser beams, circling multi-speaker sound systems, fanciful updated techno-sounds, and new pop singers. The "me generation" emerged, and the "beat crowd" and "flower children" were trading their torn jeans for designer labels. Television's MTV, the sophistication of technology, computers, and the Internet would capture the time and imagination of teenyboppers, making the Beatles and Elvis look like granddaddies.

To keep up with the times and yet retain The Intersection's old homey appearance – what a challenge. We needed to respect earlier musical renditions, but also give way to lively new recordings that made you want to dance. New ideas are the lifeblood of sustaining any business, and we needed to reach out in ways that did not appear obviously commercial. After all, we still viewed The Intersection as the antidote to commercialism. We expanded in other ways, catering with ethnic foods and entertainment, promoting performances and concerts. However, our core clientele was ageing, getting married, raising families, traveling, and joining the mainstream of American culture. The new crowds were not as imaginative: reaching them required publicity and advertising, but The Intersection was not a place you advertise. We had grown by word of mouth. Rudy and I swore that, if push came to shove, we would close the doors before failure arrived. And so, in 1985, we did what we needed to do, and moved on.

Epilogue

After our closing, the Los Angeles Times featured The Intersection in a major cover story. I wrote to thank them and simply remarked that it was a shame that the LA Times was more interested in funerals than in life.

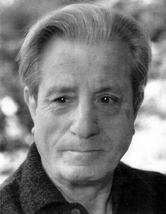

Athan Karras

This article is used with the kind permission of Ron Houston

and the Society of Folk Dance Dance Historians (SFDH).

It was published in the 2002 Folk Dance Problem Solver.